“[17] And one of the multitude answered and said, Master, I have brought unto thee my son, which hath a dumb spirit; [18] And wheresoever he taketh him, he teareth him: and he foameth, and gnasheth with his teeth, and pineth away: and I spake to thy disciples that they should cast him out; and they could not.”

Gospel According to Mark, IX, 17-19

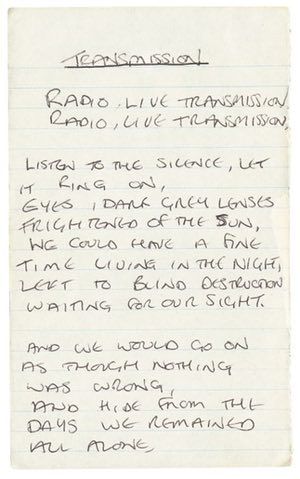

“For entertainment they watch his body twist (…) But the sickness is drowned by cries for more. Pray to God, make it quick, watch him fall.”

Ian Curtis, The Atrocity Exhibition

“[26] And crying out and convulsing him terribly, the spirit came out. And the boy was like a corpse, so that most of them said, ‘He is dead.’ [27]

Gospel According to Mark, IX, 26-27

Every cult is created in synergy with its representation. The iconography of Joy Division is like their career. Limited, hyper-condensed, built through subtraction, where the smaller the mass, the greater its energy. Three years, four if you consider the time spent under other names, and then it ends. A finite number of photographs, even rarer are the video recordings. Within this visual body, Ian Curtis always erases what surrounds him. The other band members become peripheral silhouettes, difficult to remember in detail. All witnesses who witnessed their auroral moments agree that “the band sounded like crap, but there was something about the singer.”

GLAM AND PUNK BEGINNINGS

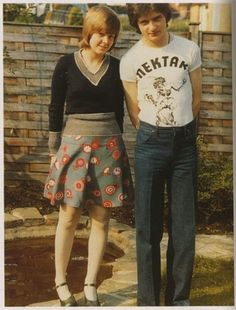

Over the course of the four years of activity, Ian Curtis’s style underwent changes. In the invisible territories before fame, during adolescence, Curtis emulates Bowie.  He cuts his hair in the style of Diamond Dogs, applies eye makeup, and wears awful red satin pants, a green shirt with Lou Reed, a fake fur from his sister. Then, in parallel with the band’s history, Ian evolves into a punk singer. Warsaw was a very raw group, according to Paul Morley, “possessing an eccentric boldness, a twinkling evil charm.”

He cuts his hair in the style of Diamond Dogs, applies eye makeup, and wears awful red satin pants, a green shirt with Lou Reed, a fake fur from his sister. Then, in parallel with the band’s history, Ian evolves into a punk singer. Warsaw was a very raw group, according to Paul Morley, “possessing an eccentric boldness, a twinkling evil charm.”

In this early period, Ian delivers wild performances emulating his idol Iggy Pop, rolling around on glass shards, inflicting cuts on his legs, throwing torn boards at the audience. He wears leather pants, rough sweaters, mirrored sunglasses with teardrop lenses, modulating his voice with rough registers.

In this early period, Ian delivers wild performances emulating his idol Iggy Pop, rolling around on glass shards, inflicting cuts on his legs, throwing torn boards at the audience. He wears leather pants, rough sweaters, mirrored sunglasses with teardrop lenses, modulating his voice with rough registers.

His wife, Deborah, recalls a jacket with the word HATE in orange acrylic on green fabric. This item is represented in black and white in the film Control, in a memorable shot from behind, with the camera following the character like a dark, impending force.

His wife, Deborah, recalls a jacket with the word HATE in orange acrylic on green fabric. This item is represented in black and white in the film Control, in a memorable shot from behind, with the camera following the character like a dark, impending force.

Carole Curtis, his sister, doesn’t have memories of this jacket but doesn’t rule out that it could have been a patch that was occasionally added and removed.

Carole Curtis, his sister, doesn’t have memories of this jacket but doesn’t rule out that it could have been a patch that was occasionally added and removed.

Other sources talk about an intoxicated Ian, fueled by alcohol and amphetamines, wearing the Hate jacket, present at the historic Sex Pistols concert in ’76 at Manchester’s Electric Circus, where the future Joy Division were essentially founded. Carole Curtis, however, states that Ian “had too much style for the punk look. He was very fashion-conscious, chic, and modern. He was always ahead of others.”

Other sources talk about an intoxicated Ian, fueled by alcohol and amphetamines, wearing the Hate jacket, present at the historic Sex Pistols concert in ’76 at Manchester’s Electric Circus, where the future Joy Division were essentially founded. Carole Curtis, however, states that Ian “had too much style for the punk look. He was very fashion-conscious, chic, and modern. He was always ahead of others.”

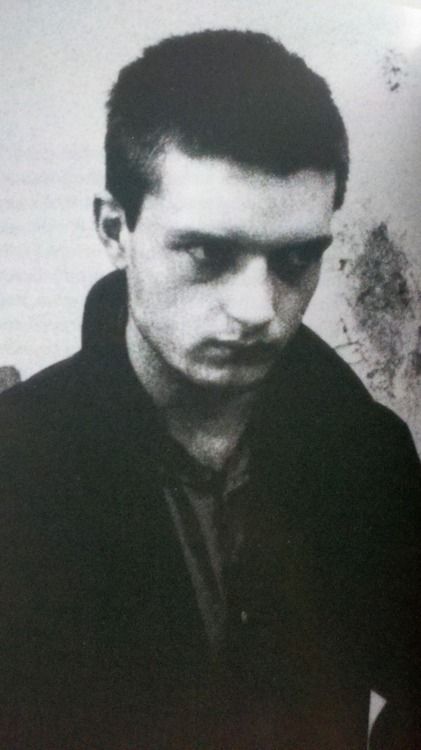

CODIFYING THE POST-PUNK AESTHETICS

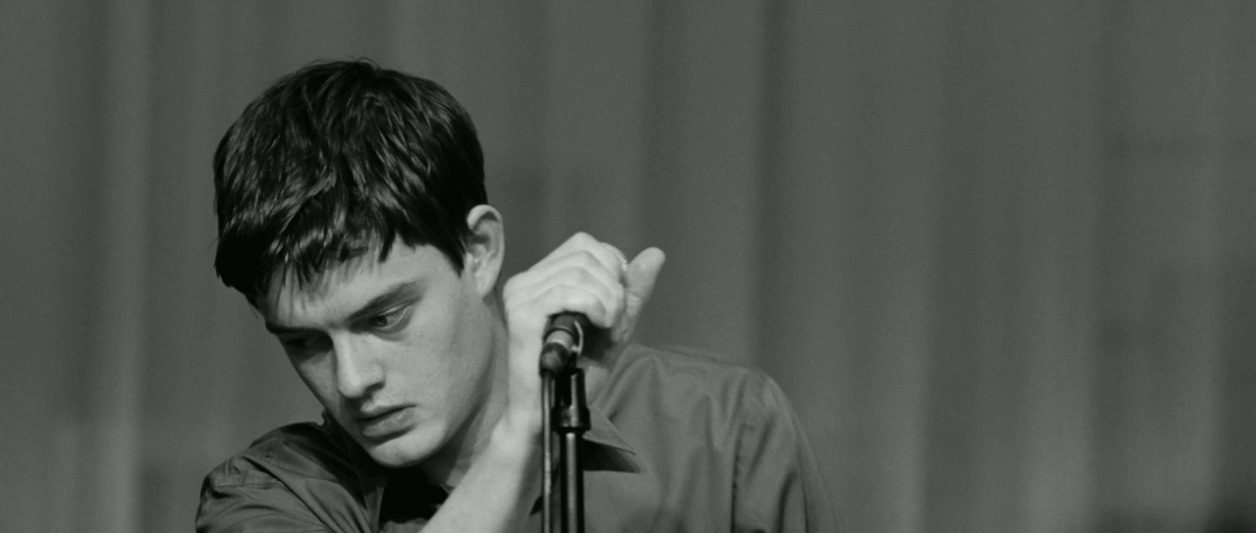

Indeed, Ian Curtis would go on to codify the trend that followed punk. Post-punk is characterized by minimalism, and dominated by shades of gray. It’s a style that tends towards mimicry in relation to the establishment, reminiscent of the mods who could wear their ritualistic clothing to work without anyone noticing. In post-punk, there are signs of subterranean aggregation, like the gray raincoats, precisely launched by Curtis in the photographs of Kevin Cummins. (The raincoat in question was actually military green.)

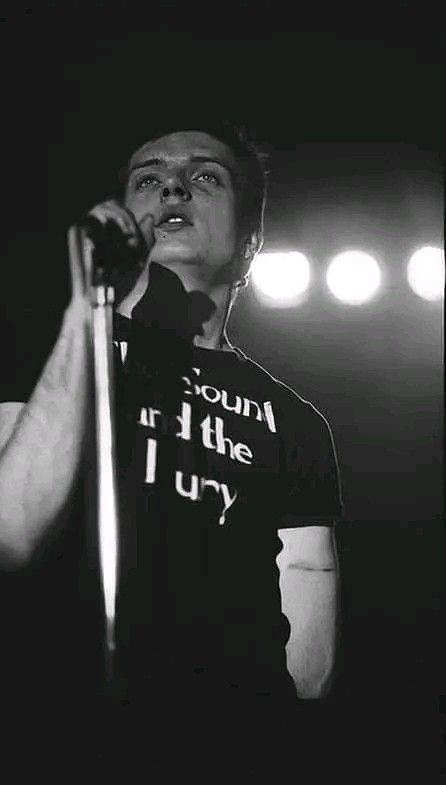

With Joy Division, the first visual deconstruction of the rockstar stereotype is carried out, resulting in a band that resembles “a group of Mormons visiting from Iowa” (Middles). Curtis abandons leather punk pants for classic men’s pants, paired with a shirt that could be gray, red, pink, or periwinkle, as seen in BBC recordings.

A simple and essential ensemble, adopted by many, from Simon Topping of A Certain Ratio to Nick Cave and Cristiano Godano of athe Italian 90s noise rock band Marlene Kuntz.

A simple and essential ensemble, adopted by many, from Simon Topping of A Certain Ratio to Nick Cave and Cristiano Godano of athe Italian 90s noise rock band Marlene Kuntz.

Another trend launched by Curtis is that of the book bag. Exceptionally cerebral, highly educated despite leaving formal studies, his lyrics are rich in avant-garde literary references. Curtis was seen backstage at the Leigh Rock Festival reading Sartre’s “Age of Reason” and walking around with his favorite volumes in a shopper bag. He loves Camus, Burroughs, Ballard, Kerouac, and Dostoevsky. Ian Curtis was the first literate punk, and even this trait of his created a trend at the time.

Another trend launched by Curtis is that of the book bag. Exceptionally cerebral, highly educated despite leaving formal studies, his lyrics are rich in avant-garde literary references. Curtis was seen backstage at the Leigh Rock Festival reading Sartre’s “Age of Reason” and walking around with his favorite volumes in a shopper bag. He loves Camus, Burroughs, Ballard, Kerouac, and Dostoevsky. Ian Curtis was the first literate punk, and even this trait of his created a trend at the time.

ON STAGE POSSESSION

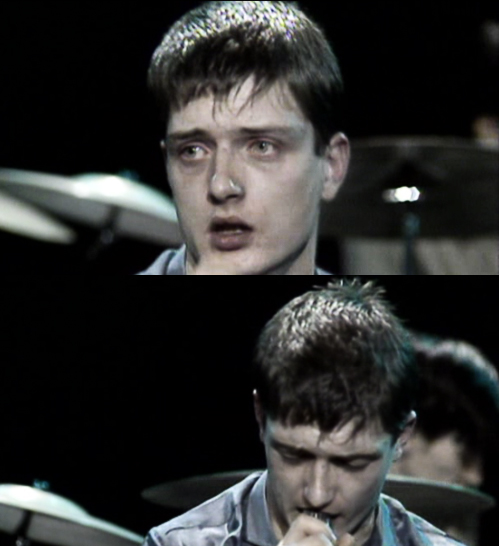

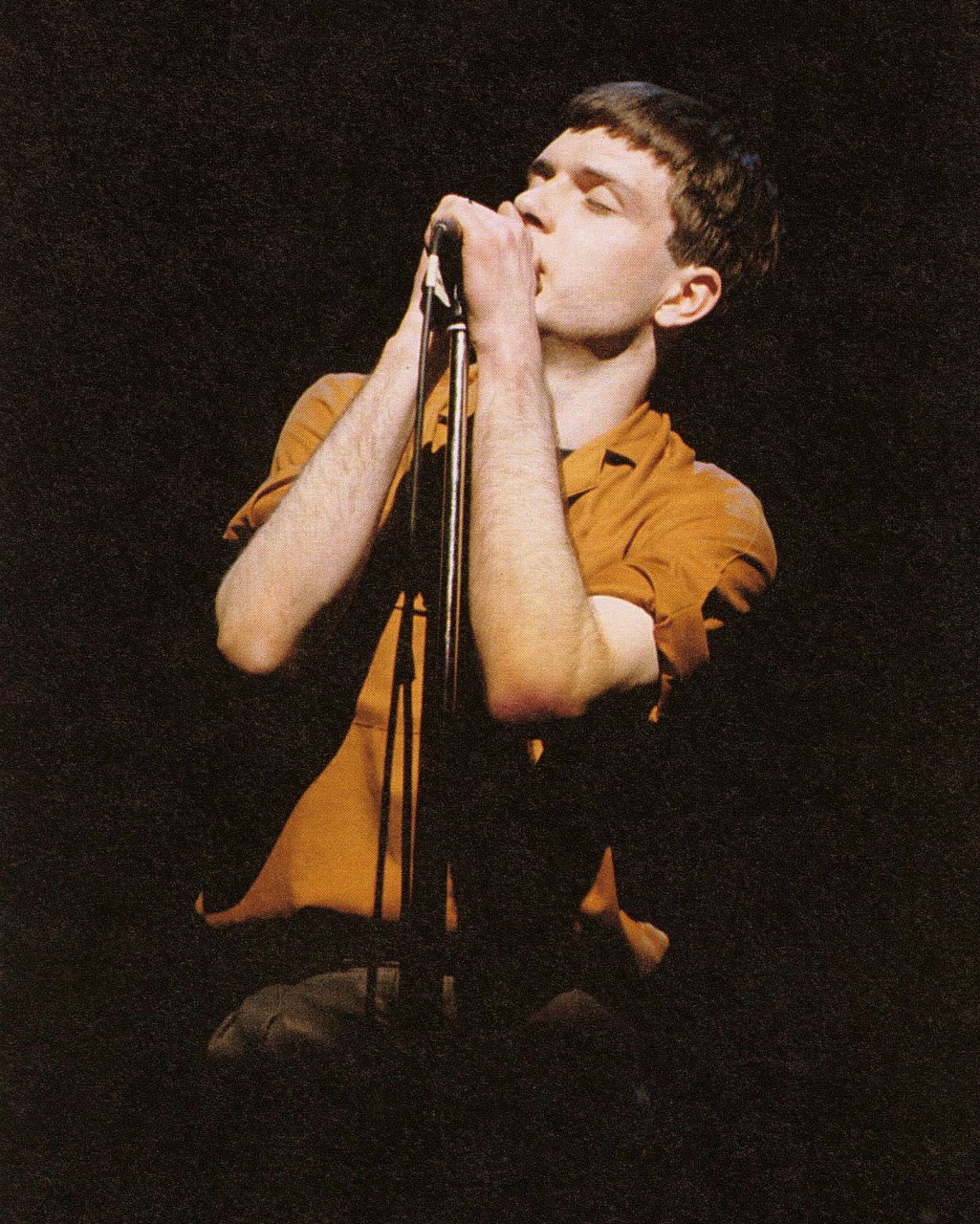

However, the most intense moments for Joy Division’s myth-making occur on stage. “When Ian danced, Joy Division instantly became the best band.” Anton Corbijn says that on the stage, Ian Curtis “became a different person as if possessed by some strange force.” “As if he were sucked into a cloud of high-voltage electric,” adds Genesis P-Orridge, a close friend of Curtis and one of the last to speak to him on the phone on the evening of May 17, 1980. “He seemed separated from others by a flash of light.” Tony Wilson, the Factory boss, goes even further: “He seemed strange and special, not for the way he danced. For his eyes.”

ICONOGRAPHY

Tall, narrow shoulders, large knotted hands, angular face, unusual nose, beautiful eyes, the aesthetic nature of Ian Curtis is twofold. Just like his personality and life on the brink of its end, divided and bipolar on one side, split on the other, between wife and lover, bourgeois family and star projection, between the yearning for success that required the spotlight and an illness that worsened due to live performances. No one managed to heal this fracture. This division for Curtis was a stigma, an evident mark in his entire phenomenology, or everything visually related to him. Depending on the angle, the period, the light, Curtis could appear beautiful due to his extraordinary intensity, with an otherworldly and sun-allergic pale luminosity, but also ugly in contorted poses, with features swollen due to neuroleptics.

His stage movements were embarrassing, grotesque, yet full of hypnotic magnetism, as captured by Kevin Cummins’s photographs. In video recordings, his expressions ranged from frenzied contortions to moments of introspection where the outside world seemed to disappear from his eyes. These expressions were very sensual, defined by the exclusive concentration typical of sex. Aesthetic-wise, no one managed to teeter on the razor’s edge between ugliness and splendor quite like Ian Curtis did.

BIOGRAPHIES AND SIMULACRA

His biographical representation is divided between his wife’s book, Deborah, which describes Ian as an unstable opportunist, pathologically jealous, racist, and with a pronounced streak of violence, and the biography by Mick Middles, a historic post-punk journalist, in which everyone agrees on the portrait of a selfless, calm man with great sensitivity and empathy. Twenty years later, the icon of Ian Curtis crystallizes into two simulacra in the films “Control” (Anton Corbijn, 2007) and “24 Hour Party People” (Michael Winterbottom, 2002).

On one hand, actor Sam Riley, with large eyes and delicate features, delivering a lyrical performance, and on the other, Sean Harris, with a squinting gaze and a twisted face, horrifying as he lies in a white-clad coffin, yet better at portraying moments of possession on stage than Riley.

On one hand, actor Sam Riley, with large eyes and delicate features, delivering a lyrical performance, and on the other, Sean Harris, with a squinting gaze and a twisted face, horrifying as he lies in a white-clad coffin, yet better at portraying moments of possession on stage than Riley.

This very division, this polarization, is captured by Corbijn in the posthumous video for “Atmosphere.” Mysterious like a post-mortem vision, the video depicts a desolate land inhabited by faceless monks, black and white figures reminiscent of an Ingmar Bergman film. The hooded figures carry Curtis icons, and on their backs are imprinted two symbols, a plus sign and a minus sign. The procession ends, and the viewer realizes that what seemed like a desert is actually the path leading to the sea, emblematic of all the mysteries of life and death and everything that eludes our understanding.

This very division, this polarization, is captured by Corbijn in the posthumous video for “Atmosphere.” Mysterious like a post-mortem vision, the video depicts a desolate land inhabited by faceless monks, black and white figures reminiscent of an Ingmar Bergman film. The hooded figures carry Curtis icons, and on their backs are imprinted two symbols, a plus sign and a minus sign. The procession ends, and the viewer realizes that what seemed like a desert is actually the path leading to the sea, emblematic of all the mysteries of life and death and everything that eludes our understanding.

This article was written in Italian several years ago, and the quotes included were taken from ‘Touching From a Distance’ by Deborah Curtis and ‘Torn Apart: The Life of Ian Curtis’ by Mick Middles, both in their Italian editions and translations. During the English translation of our article, as we did not have access to the English versions of these books, it proved impossible to find the original quotes, even after searching multiple sources such as Google Scholar, and others. For these reasons, we chose to maintain the translation of our original text within quotation marks, as if they were direct quotes. We would be grateful if someone could provide us with the original versions.

Bibliography

If you enjoyed this article and are interested in delving deeper into the topic, you can find some bibliography in the following links. If you appreciate our content and would like to support the activities of our site, you can make purchases through these links, not necessarily limited to books listed in the bibliography but any kind of item. To do so, simply access the link and then fill your cart. Thanks to everyone!

Mick Middles and Linsday Reade, Torn Apart: The Life of Ian Curtis

Deborah Curtis, Touching from a Distance, Ian Curtis & Joy Division

Michael Winterbottom, 24 Hour Party People

Joy Division, Unknown Pleasures

_The very next article will be the second part of our history of the Kindred Creatures and Other Goth 80s’ Subcultures in Italy, with a focus on concerts, rituals and places of aggregation.

Stay tuned!_