Gothic Specificity and Autonomous Paths

Gothic Specificity and Autonomous Paths

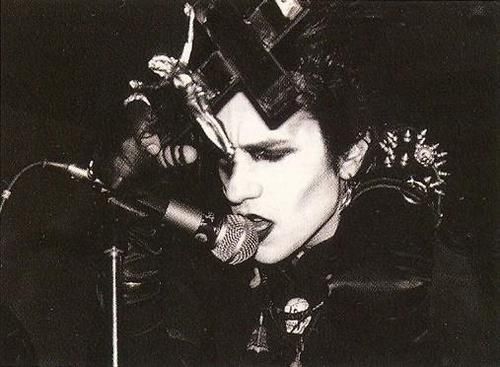

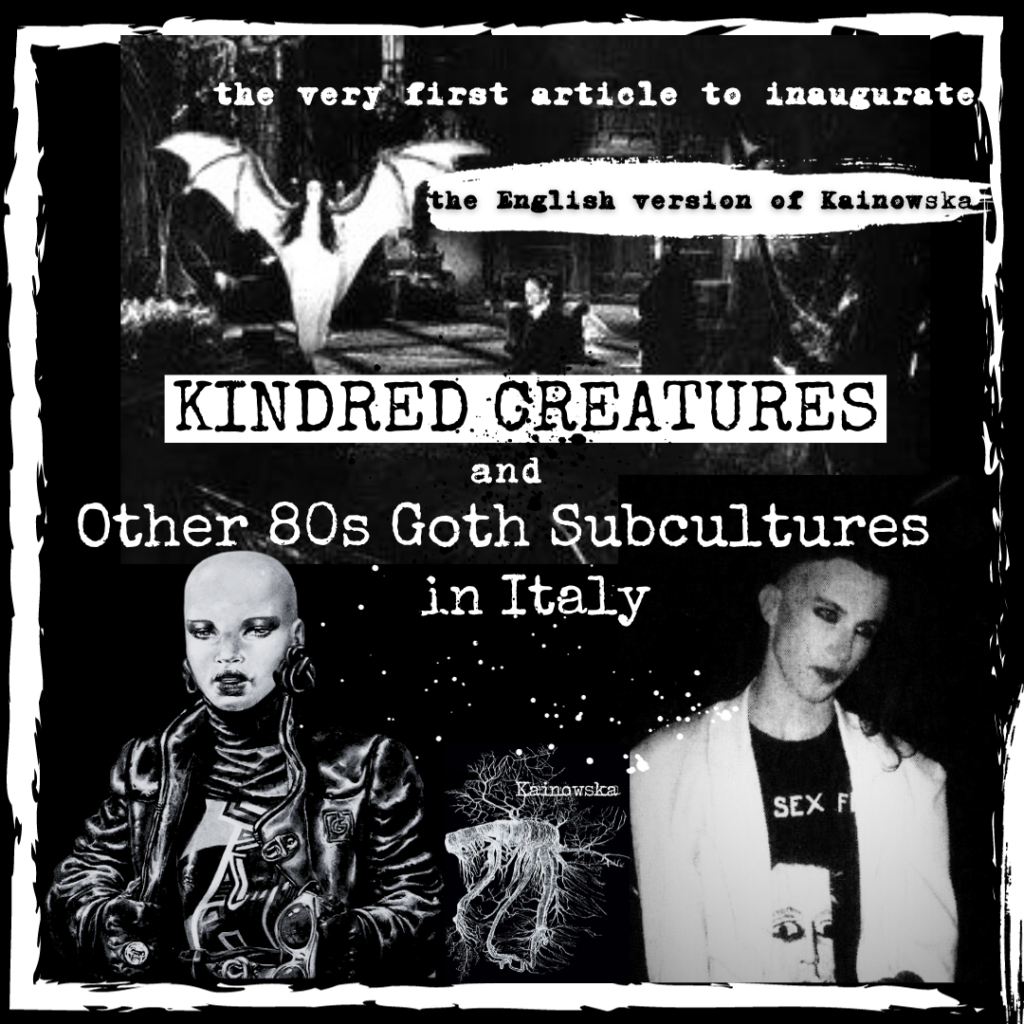

The very first Italian goths are, as we saw in the first part of this article, absolute outsiders, both from the society of forced hedonism and the superficial well-being of 1980s Italy, as well as from the mode of direct confrontation and hyper-politicized behavior script of the punks. Many of those who will become the protagonists of the goth scene are united by a freakish and problematic nature: family problems, depression issues, struggles with violence management, and eating disorders. In comparison to the tougher punks who reject everything society has to offer, from work to education, the majority of early goths have a higher level of education. Many attend high school or university. A specific type of culture is crucial to the identity of those belonging to this subculture, and it cannot be separated from knowledge of art. Thus, Decadence, Existentialism, Surrealism, and Dada constitute the ABCs of being goth.

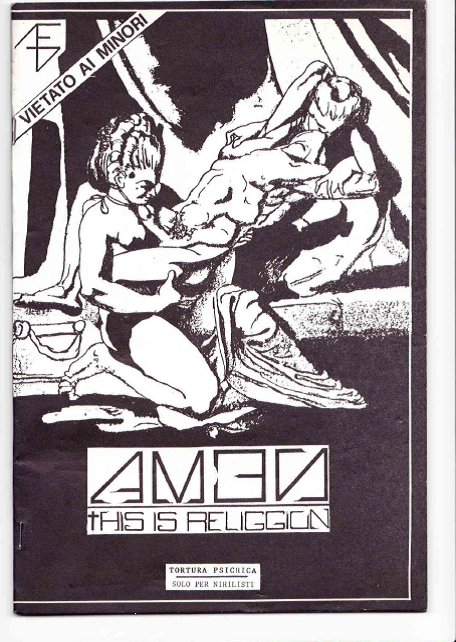

Before 1983, there is no recognizable group of goths in Milan. This new subculture goes through various stages of gestation and development: a phase of aesthetic rupture with the dominant canon, which they share with punks along with other ideals (such as anti-militarism); a sense of only partial belonging to more radical ways of life; a turning inward where autonomous tastes and solitary artistic practices like writing are developed. The gothzines Fame and Amen, edited and created by Angela Valcavi along with other collaborators – who we will delve into in detail in the following part of this article- are born before anything else, and they will become a sort of primary magical object around which initiatives leading to the birth of the Kindred Creatures subculture will be structured.

Another crucial aspect of this goth subculture is the dimension of exploration, stemming from not fully identifying with either the dominant culture or the existing subcultures. Thus, one must search for something to identify with, whether it’s music different from hardcore or other cultural, artistic, or literary inspirations. Essentially, it’s a quest for one’s own roots.

THE EARLY CONCERTS, THE BLACK TIDE, THE KINDRED CREATURES

While the antagonists opt for secession, the early goths still want to construct their own personal heterotopia. Roxie, a protagonist of the scene, explains: “Compared to the more politicized punk, there isn’t a direct fight in the goth scene: it was more about creating your own parallel world. It’s secession: from active resistance to passive.”

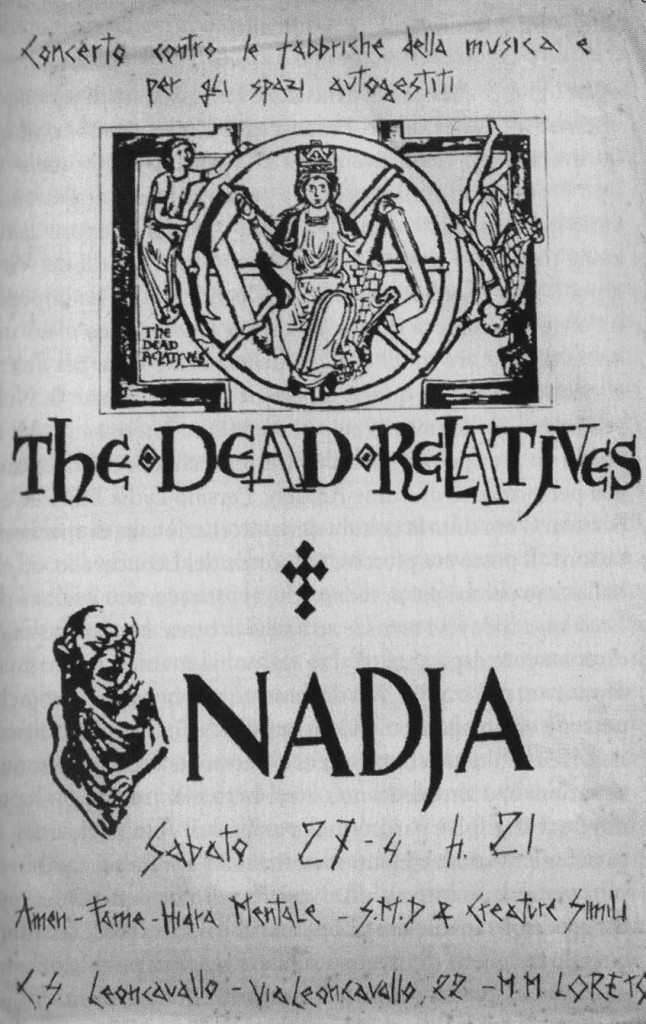

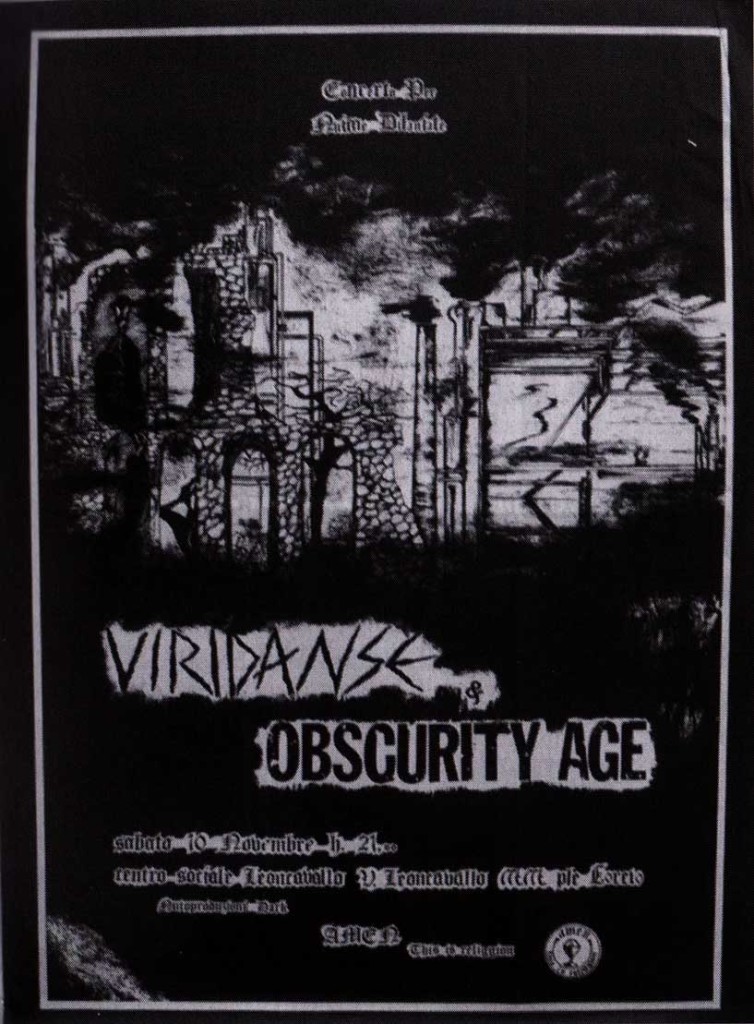

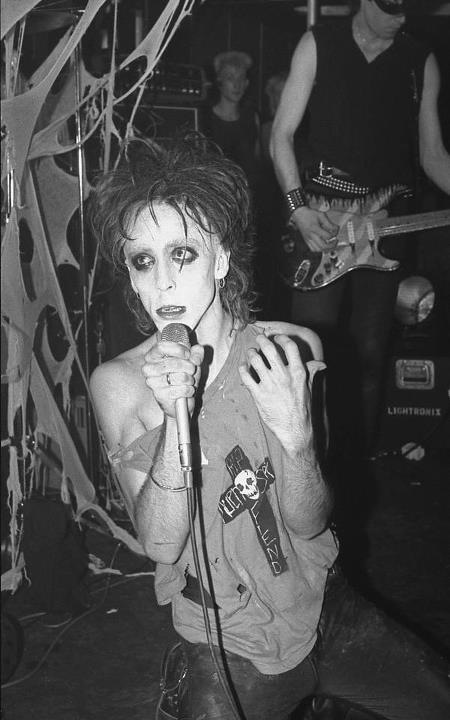

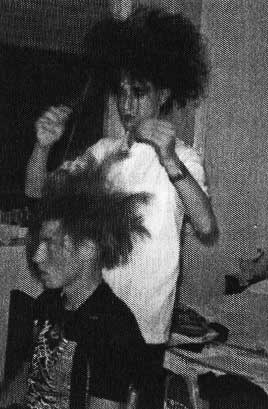

Through the promotional efforts of the gothzine Amen, Angela Valcavi, Lia, Atomo, and Vincillo come into contact with the scene of the wild bar-dairy Strafalari, where “brilliant readings that nobody gives a damn about.” take place, located in front of the famous Leoncavallo squat. Thus, the Kindred Creatures, passing through the assembly committee meeting, manage to organize the first concert on November 10th, 1983. The lineup includes Obscurity Age from Milan and Viridanse from Alessandria. Those from the Leoncavallo can’t believe their eyes when they see about a thousand people showing up, a real “black tide.”.

Angela Valcavi recounts: “We discovered a whole universe of individuals dressed in black. The feeling that these people finally found themselves in an environment where they could identify was tangible. For the first time, we saw so many individuals gathered who probably had a lot in common, who had developed shared interests in a discreet, intimate manner, linked to closed environments. (…) At that moment, there wasn’t yet a circuit, and it was surprising to see so many people united by an identity.“

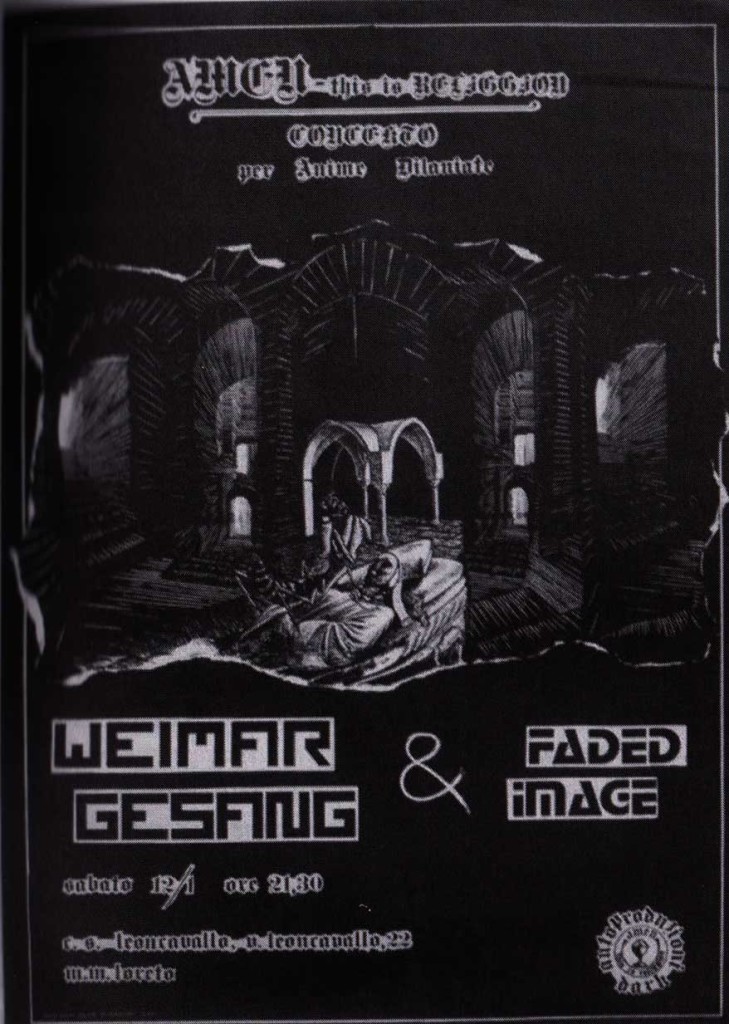

On January 12th, 1984, the second concert takes place, featuring Weimar Gesang and Faded Images.

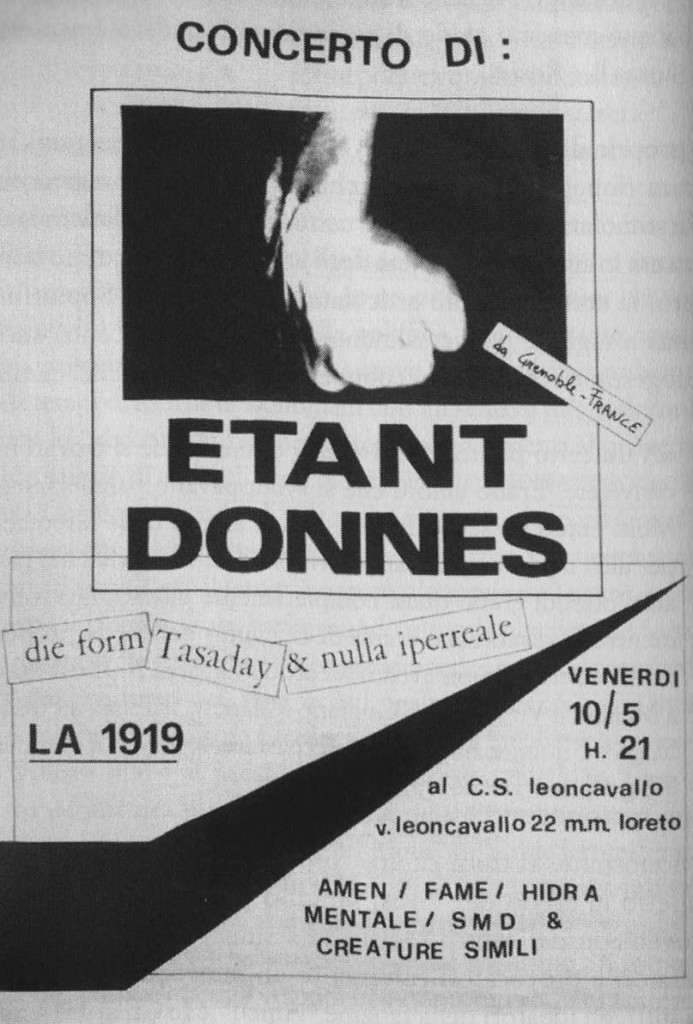

At the third initiative organized at the Leoncavallo, Voices and Art of Waiting perform. The fourth concert is endorsed by the titles of the gothzines Amen, Fame, Hydra Mentale, S.D.M., and Kindred Creatures, whose collective was born at the beginning of that year within the Virus. “We liked the name Kindred Creatures because the term ‘creature’ makes you think of creation, something that wasn’t there before and through a gesture, an act, begins to exist. It evokes a journey, artistic and philosophical. “Kindred” instead refers to resemblance, closeness to a path: it conveys the idea of identity and sharing.” (Angela Valcavi)

The Kindred Creatures began to show up more often on Via Torino, at the Sinigaglia fair, at the Columns of San Lorenzo, which were then the most alternative meeting places in Milan. They stage a flash mob with bloody performances at the conference on youth gangs at Palazzo Isimbardi, where they earn political respect from even the most extreme punks. Later, on May 5th, 1984, the Kindred Creatures attempted an occupation of the Teatro Miele, a beautiful abandoned place where concerts by Area and Skiantos had taken place, but they were evicted in less than a day.

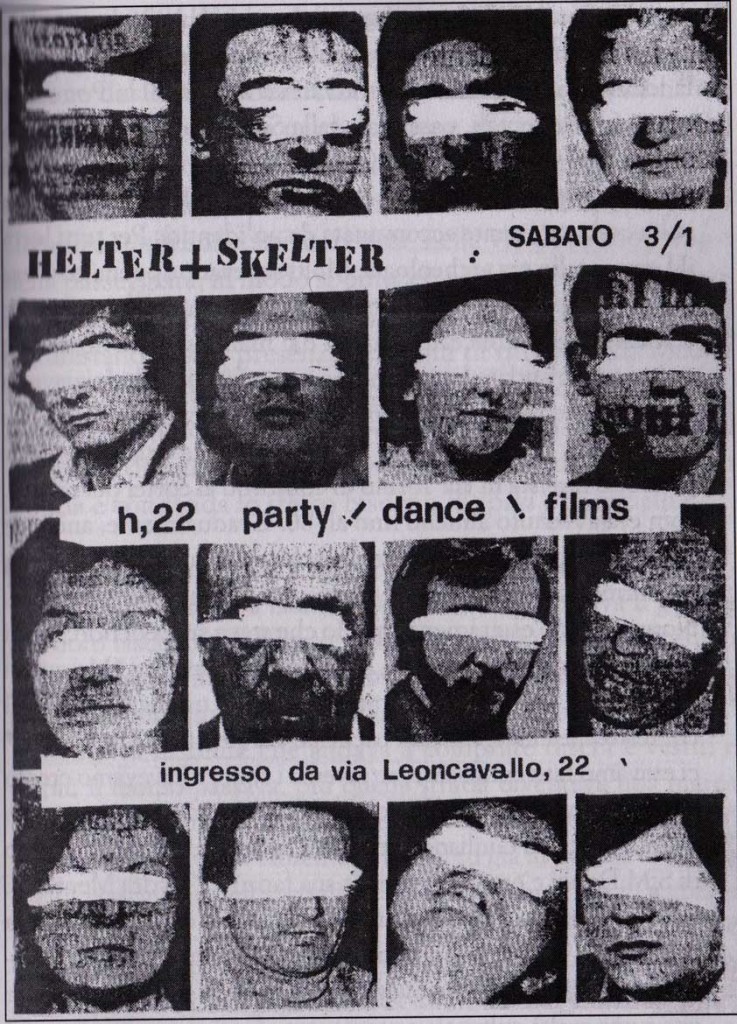

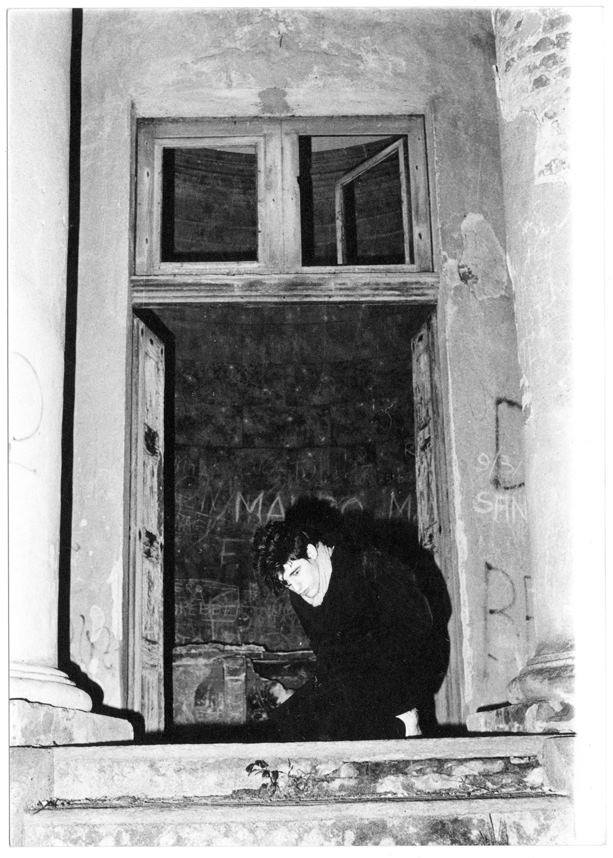

HELTER SKELTER AND DECODER

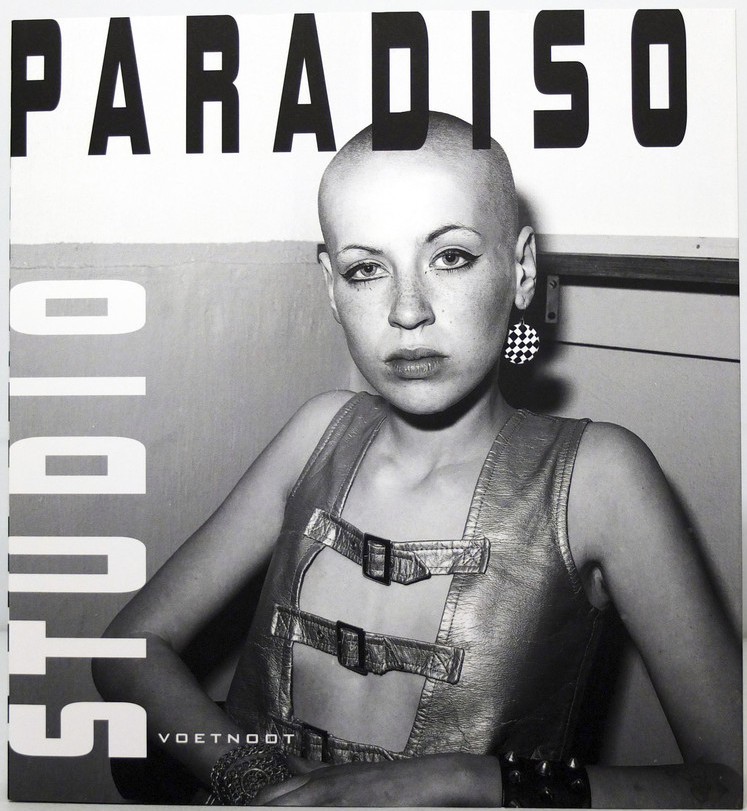

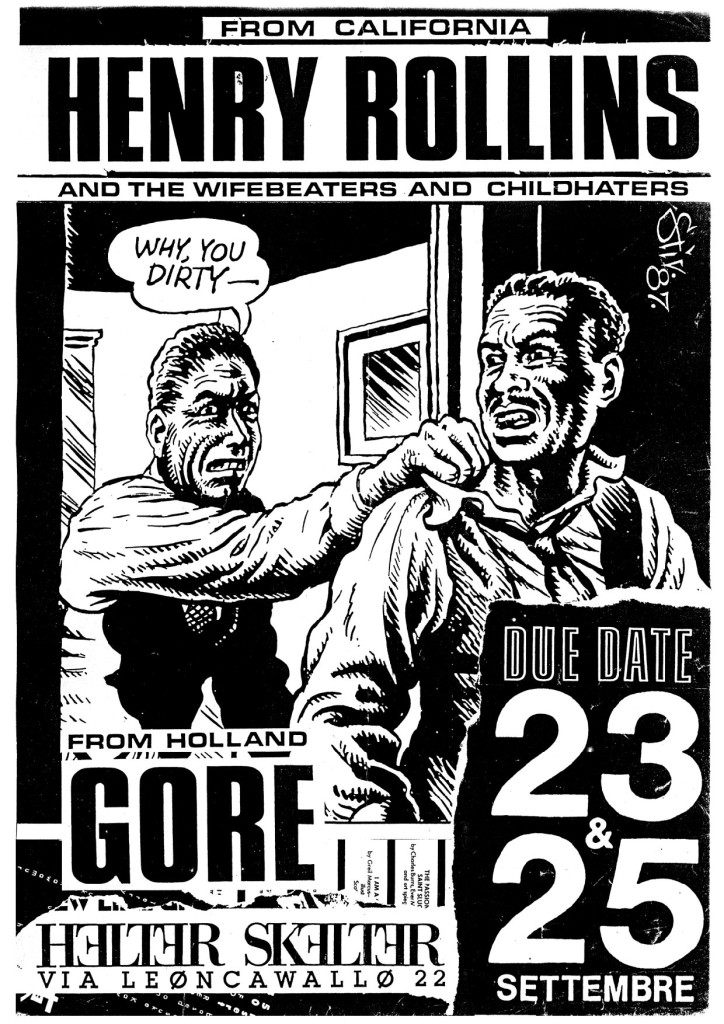

In the end, the collective from Leoncavallo grants this proto-goth group the management of a basement in an adjacent building. This is how the self-managed space Helter Skelter is born, which will become the home of the Kindred Creatures. The name conveys chaos, vertigo, war of worlds, bringing together Charles Manson, the Beatles, and Siouxsie and the Banshees. The reference model is the Paradiso venues in Amsterdam and the Kukuk, an occupied place in Berlin.

In the end, the collective from Leoncavallo grants this proto-goth group the management of a basement in an adjacent building. This is how the self-managed space Helter Skelter is born, which will become the home of the Kindred Creatures. The name conveys chaos, vertigo, war of worlds, bringing together Charles Manson, the Beatles, and Siouxsie and the Banshees. The reference model is the Paradiso venues in Amsterdam and the Kukuk, an occupied place in Berlin.

At Helter Skelter, the cultural offerings are very diverse; they organize concerts, exhibitions, film forums.

At Helter Skelter, the cultural offerings are very diverse; they organize concerts, exhibitions, film forums.

At Helter Skelter, the Kindred Creatures organize politically low-priced concerts for the first Italian goth groups, as well as for Henry Rollins and Sonic Youth, who are hosted to sleep at Joykix’s house in Rogoredo.

Gomma, a punk of the Virus squat and a central figure in the Italian cyberpunk scene, describes the impressions of (and on) Henry Rollins at the Helter Skelter: ‘The gig is also mentioned by Rollins himself in one of his poetry books, describing Helter Skelter as super-underground, a place with a carpet made of empty beer cans and nomadic punks rummaging through bins in search of food. He kept quite a distance, peeking from the side, and in the morning, he went jogging, a practice completely unfamiliar to us. But he stood on stage like Satan himself. It was insane. He sweated like few others, and being literally soaked, the microphone would give him electric shocks, which he shielded himself from with a T-shirt wrapped around it. It was also damn cold (we were without windows), but he never complained. And that proves he’s killer.”

They screen film retrospectives by Richard Kern. , which elicits many perplexed faces among the comrades.

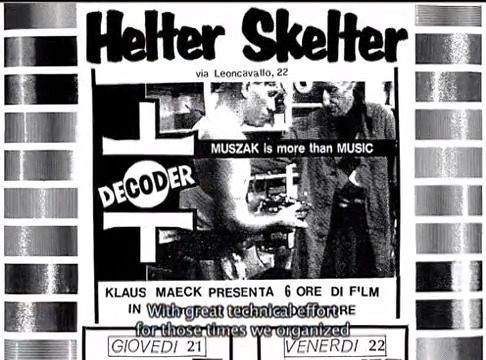

They screen film retrospectives by Richard Kern. , which elicits many perplexed faces among the comrades.  At the premiere of Decoder, a lysergic dystopia on media and control featuring Christiane F., William Burroughs, and Genesis P-Orridge, director Klaus Maeck is also present, along with an audience of around 300 people.

At the premiere of Decoder, a lysergic dystopia on media and control featuring Christiane F., William Burroughs, and Genesis P-Orridge, director Klaus Maeck is also present, along with an audience of around 300 people.

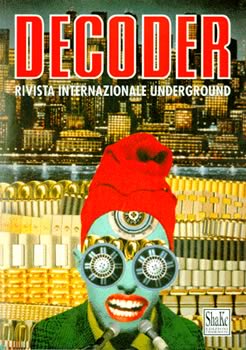

Shortly thereafter, some Kindred Creatures will move into cyberpunk, creating an international underground magazine that adopts the name Decoder. Decoder is distinguished by the illustrations of Professor Bad Trip and deliberately chooses to ignore the classic Italian post-communist debates to theorize further concepts. One of these is the concept of imaginative suffocation, the impossibility of imagining alternatives to the existing, stemming from repression and retrenchment. Decoder is a decoder, to understand the code of the present and be able to reverse it. All of this originates within Helter Skelter, and Joykix, one of the Kindred Creatures, is part of the editorial team.

Shortly thereafter, some Kindred Creatures will move into cyberpunk, creating an international underground magazine that adopts the name Decoder. Decoder is distinguished by the illustrations of Professor Bad Trip and deliberately chooses to ignore the classic Italian post-communist debates to theorize further concepts. One of these is the concept of imaginative suffocation, the impossibility of imagining alternatives to the existing, stemming from repression and retrenchment. Decoder is a decoder, to understand the code of the present and be able to reverse it. All of this originates within Helter Skelter, and Joykix, one of the Kindred Creatures, is part of the editorial team.

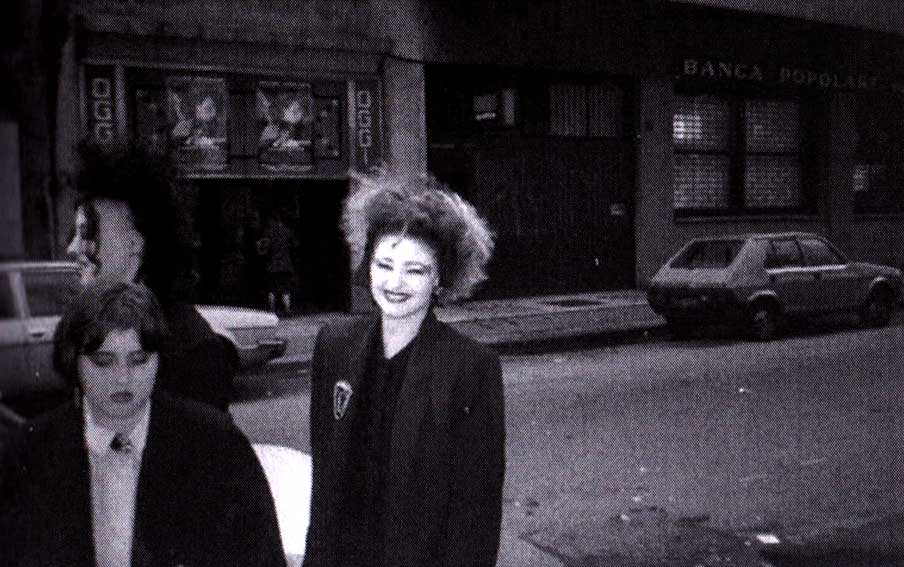

The comrades of Leoncavallo are amazed by the huge influx at Helter Skelter, characterized by a melting pot of diverse individuals, typical of superlative venues in their golden moments. Alongside the Kindred Creatures, inside the Helter Skelter you can find the comrades of Leoncavallo from the 1970s, the punks orphaned by the recently evicted Virus, the style-conscious goths who mostly frequent the nightclub circuit, Polish goths who whip themselves, Slovak goths exchanging ideas about self-managing cultural initiatives.

The comrades of Leoncavallo are amazed by the huge influx at Helter Skelter, characterized by a melting pot of diverse individuals, typical of superlative venues in their golden moments. Alongside the Kindred Creatures, inside the Helter Skelter you can find the comrades of Leoncavallo from the 1970s, the punks orphaned by the recently evicted Virus, the style-conscious goths who mostly frequent the nightclub circuit, Polish goths who whip themselves, Slovak goths exchanging ideas about self-managing cultural initiatives.

There are performances by Annie Anxiety, and one day Lydia Lunch is spotted.

There are performances by Annie Anxiety, and one day Lydia Lunch is spotted.

The Helter Skelter closed in ’87, a terrible year for everything that is the Milanese underground, which also saw the definitive closure of the second Virus.

The Helter Skelter closed in ’87, a terrible year for everything that is the Milanese underground, which also saw the definitive closure of the second Virus.

GOTHS OF THE DISCOS AND THE HYSTERIKA CLUB

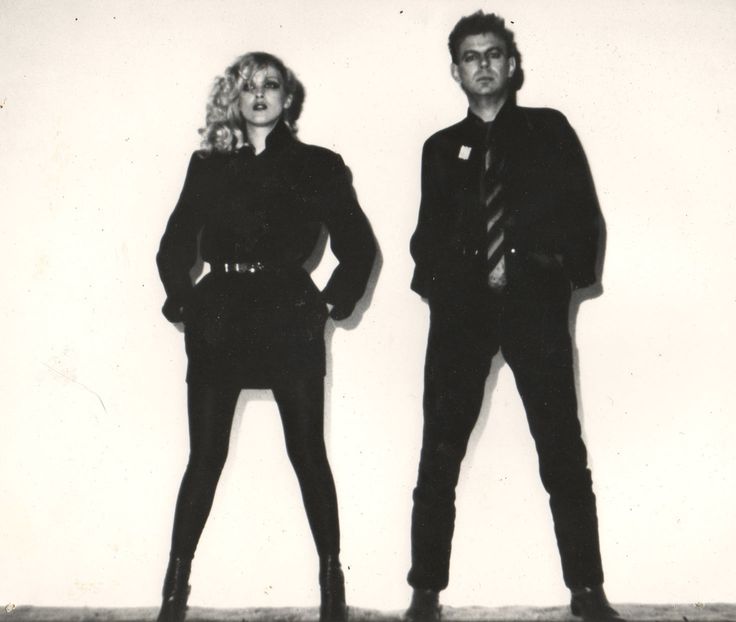

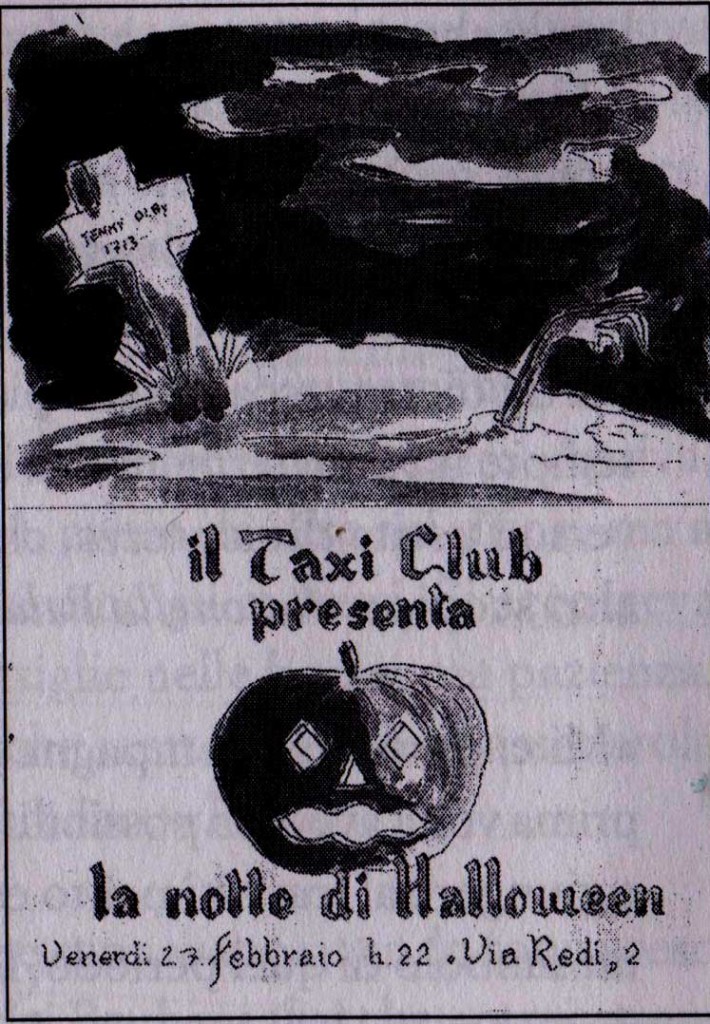

In this initial phase, there is an active exchange between the more politicized Kindred Creatures and the more commercial club scene, revolving around the cult venue Hysterika. Hysterika emerged from the ashes of Taxi, opened in 1979 on Via Redi. Taxi was a family-run establishment where the mother knitted in the coat check booth. The music selection included Talking Heads, Lou Reed, Bowie, Culture Club, Soft Cell, and Depeche Mode. The Taxi’s DJ, René, was a friend of the legendary band Krisma, appeared in Lola’s video, and introduced New Romantic fashion to Milan.

In this initial phase, there is an active exchange between the more politicized Kindred Creatures and the more commercial club scene, revolving around the cult venue Hysterika. Hysterika emerged from the ashes of Taxi, opened in 1979 on Via Redi. Taxi was a family-run establishment where the mother knitted in the coat check booth. The music selection included Talking Heads, Lou Reed, Bowie, Culture Club, Soft Cell, and Depeche Mode. The Taxi’s DJ, René, was a friend of the legendary band Krisma, appeared in Lola’s video, and introduced New Romantic fashion to Milan.  René organized Halloween events in ’82, a concept still foreign to Italy, where Halloween celebrations were virtually unheard of at the time. The Taxi attracted elegant new wavers, slicked-back rockabillies, early extravagant New Romantics, and initial goth enthusiasts, mixed with members of Depeche Mode, Visage, and Christian Death. In November ’83, the Taxi hosted the Funeral Party, recognized as Italy’s first gothic party.

René organized Halloween events in ’82, a concept still foreign to Italy, where Halloween celebrations were virtually unheard of at the time. The Taxi attracted elegant new wavers, slicked-back rockabillies, early extravagant New Romantics, and initial goth enthusiasts, mixed with members of Depeche Mode, Visage, and Christian Death. In November ’83, the Taxi hosted the Funeral Party, recognized as Italy’s first gothic party.

In 1984, the Taxi transformed into Hysterika, adopting Nina Hagen’s sulking mouth as its logo. Antonella Pala described the place as follows: “I still remember the entrance, dark, narrow, all black, with the iron door. It was a sort of basement of the venue above, next to a porn cinema. Behind the bar counter, there were sofas arranged. In front, a wall covered in handprints, writings, and lipstick kisses reflected our typical rhythmic back-and-forth dance. On the left, high above, was the DJ booth; behind, next to the dance floor, was the bathroom where there was always a lot of commotion! And on the right of the bar counter was the stairway to the emergency exit, which was often used for quite different purposes...”

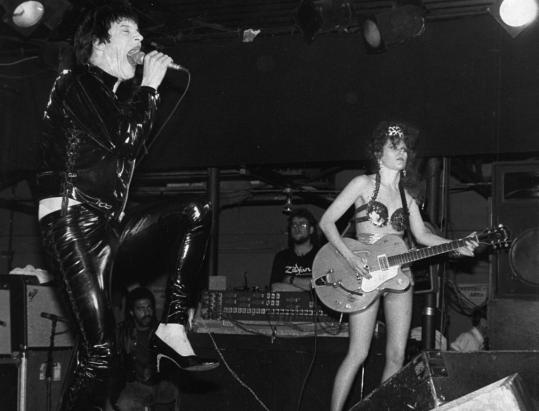

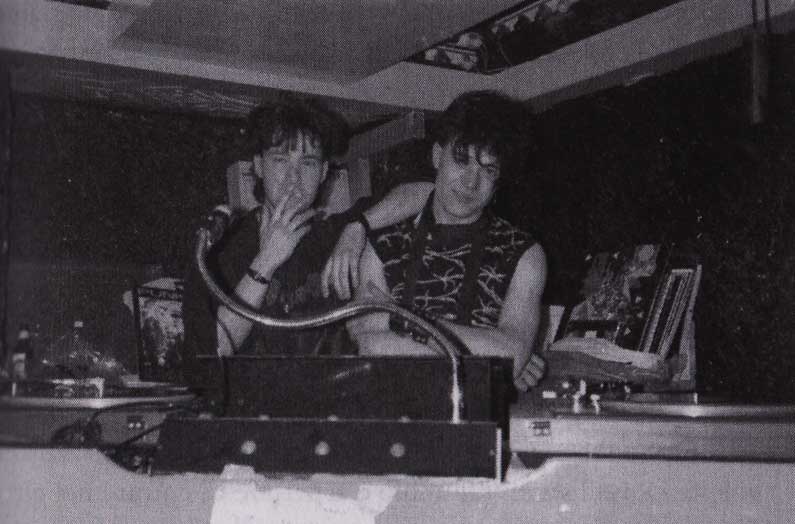

There were nights on Fridays and Saturdays with DJs Pietro Perozzi and Tannox. But the pinnacle was Sunday afternoons with the DJ duo Alex and Pino Carafa, known as DJ Lupo. Alex and Lupo played together, alternating lights and music, introducing then-unknown bands like Christian Death, CCCP, Death in June, The Cramps, and Alien Sex Fiend.

There were nights on Fridays and Saturdays with DJs Pietro Perozzi and Tannox. But the pinnacle was Sunday afternoons with the DJ duo Alex and Pino Carafa, known as DJ Lupo. Alex and Lupo played together, alternating lights and music, introducing then-unknown bands like Christian Death, CCCP, Death in June, The Cramps, and Alien Sex Fiend.

This state of grace persisted every Sunday from ’86 to ’89. Annual Miss Hysterika contests took place, where personality, not appearance, was the primary criterion for winning. People often brought concealed bottles in their bags, but the manager pretended not to notice, relying on entrance fees for revenue. Occasionally, Renè would release his chinchillas into the club, and people would scream as they accidentally sat on something alive, furry, and very miffed.

This state of grace persisted every Sunday from ’86 to ’89. Annual Miss Hysterika contests took place, where personality, not appearance, was the primary criterion for winning. People often brought concealed bottles in their bags, but the manager pretended not to notice, relying on entrance fees for revenue. Occasionally, Renè would release his chinchillas into the club, and people would scream as they accidentally sat on something alive, furry, and very miffed.

Initially, the scene was very united; everyone knew each other, sharing musical tastes, aesthetics, and interests. Various groups coexisted. However, even at Hysterika, forms of elitism began to emerge, no longer linked to political connotations but to aesthetics. The contrasts were especially felt between Milanese dark enthusiasts and those from elsewhere. Andrea from Varese recalls, “We weren’t particularly demanding in terms of appearance: we wore black jeans, boots, a coat, or a leather jacket. There, everyone wore lace and pointy shoes. It’s true, that maybe we were a bit provincial, but there was a clear difference between our way of socializing and theirs. The first few times you entered, you faced people who were aware they were the hosts, and they had a snobbish attitude toward those from outside. Many were approachable, but the hardcore group was quite snobbish. Before you could exchange a few words with them, it took a while. But ultimately, we made fun of them; we didn’t see them as idols to revere. Let’s say that, in the end, getting drunk brought everyone together.”

Initially, the scene was very united; everyone knew each other, sharing musical tastes, aesthetics, and interests. Various groups coexisted. However, even at Hysterika, forms of elitism began to emerge, no longer linked to political connotations but to aesthetics. The contrasts were especially felt between Milanese dark enthusiasts and those from elsewhere. Andrea from Varese recalls, “We weren’t particularly demanding in terms of appearance: we wore black jeans, boots, a coat, or a leather jacket. There, everyone wore lace and pointy shoes. It’s true, that maybe we were a bit provincial, but there was a clear difference between our way of socializing and theirs. The first few times you entered, you faced people who were aware they were the hosts, and they had a snobbish attitude toward those from outside. Many were approachable, but the hardcore group was quite snobbish. Before you could exchange a few words with them, it took a while. But ultimately, we made fun of them; we didn’t see them as idols to revere. Let’s say that, in the end, getting drunk brought everyone together.”

After the commercial turn of historic bands like The Cure, after DJ Lupo’s departure in ’89 and a shift of the fashion scene to the club Plastic, after the aesthetic codes of regulars and newcomers began to blend and become indistinguishable, Hysterika definitively closed in 1991.

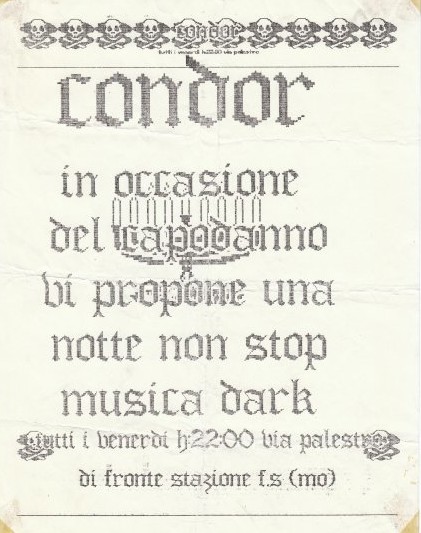

The club-goers’ scene was characterized by nomadism, with people often moving to explore dark venues in other cities, such as Modena’s Condor or Turin’s Charming, where industrial music was already played in ’86. This nomadic inclination amplified the sense of belonging.

The club-goers’ scene was characterized by nomadism, with people often moving to explore dark venues in other cities, such as Modena’s Condor or Turin’s Charming, where industrial music was already played in ’86. This nomadic inclination amplified the sense of belonging.

In addition to the Virus, the Helter Skelter, and the Hysterika on Via Redi, there are other significant places for the goth subculture in Milan. Roy recounts: “In San Giuliano Milanese, Viridis hosted events on Fridays; it was a truly beautiful place. However, it was a war there, in the sense that every time you arrived, there was someone who had a problem with you. I got beaten up everywhere. I especially remember this skinhead: Lino the Skin. He was ugly, very mean. One time he caught me. I was truly irritating the hell out of him, he couldn’t stand my guts. (…) I also remember Motion, halfway between Milan and Bergamo. This too was a beautiful place, but there were always fights there as well. (…) Until ’85-’86, it was a war in these mixed places. And it was also in the city. Going out to have fun meant coming home injured. Not dead, I don’t want to exaggerate, but injured, yes. It happened to me several times. Because in addition to stabbings and punches, I lost count of the slaps I took: my face became a bit rubbery from all the slaps I took! The situation begins to calm down a bit in the late eighties; there, you could see that something had changed in the alternative world.'”

In addition to the Virus, the Helter Skelter, and the Hysterika on Via Redi, there are other significant places for the goth subculture in Milan. Roy recounts: “In San Giuliano Milanese, Viridis hosted events on Fridays; it was a truly beautiful place. However, it was a war there, in the sense that every time you arrived, there was someone who had a problem with you. I got beaten up everywhere. I especially remember this skinhead: Lino the Skin. He was ugly, very mean. One time he caught me. I was truly irritating the hell out of him, he couldn’t stand my guts. (…) I also remember Motion, halfway between Milan and Bergamo. This too was a beautiful place, but there were always fights there as well. (…) Until ’85-’86, it was a war in these mixed places. And it was also in the city. Going out to have fun meant coming home injured. Not dead, I don’t want to exaggerate, but injured, yes. It happened to me several times. Because in addition to stabbings and punches, I lost count of the slaps I took: my face became a bit rubbery from all the slaps I took! The situation begins to calm down a bit in the late eighties; there, you could see that something had changed in the alternative world.'”

MILAN TRIBAL ZONES IN THE EIGHTIES

In this regard, Sergio from Meda recounts that Milan was divided into true tribal zones, and crossing boundaries often meant taking a beating. “In Via Torino, there was a passage where on one side there was the Standa shopping mall, and on the other, Wendy, a fast-food joint. Punks would gather on the side of Standa, while in front of Wendy, there were some goths, a few rockabillies, a couple of skins: a mixed crowd. Punks initially had an issue with us and made fun of us, calling us names like “fags”, “crowlets”, and the like. Nothing happened, but rather than having trouble with punks, you would pass to the side of the skins. Two years later, everything was completely different: the skins kicked you, called you “commies”, and you couldn’t pass through there anymore. On Corso Vittorio Emanuele, in front of the old wall, there were skaters, the first breakdancers, and even some paninari preppies a bit further back. Metalheads, on the other hand, were in a little alley behind Palazzo Reale, at the Transex store. Practically on Via Torino, where there is now the bookstore before the pharmacy, there were the rockabillies, while before the Columns, on the right, where now there is the wine shop, back then there was the Oktober Fest beer hall, and that’s where the real skins were, the ones who really threw punches, so you had to take a detour to get to the shops. You couldn’t pass through there: if you passed on the other side, they pretended not to notice, but if you walked in front of them, you’d get at least a slap. At least. And around ’86-’87, things started to get even heavier. Similar incidents had happened before; in ’85, for example, at the old wall, skins from Zurich had arrived and sent a couple of people to the hospital, badly beaten. They cracked a few skulls, and I think that contributed to breaking up that group. (…) When I hear goth people today saying they are right-wing, it makes me laugh, and it also surprises me a bit: we were always hated by those on the right; all right-wing movements considered us enemies. With rockabillies, we had some issues, but those were more about teasing. With the motorcycle gang, however, no problems: some of them liked kraut-rock, German electronic music, so they occasionally came to Hysterika. But they kept to themselves: you weren’t supposed to bother them, or else you were in trouble, but they didn’t come to bother you. The same goes for metalheads: you went to Transex to buy a couple of studs, we didn’t look at each other very well, but we never had problems with a metalhead. Also on Vittorio Emanuele, on the left, towards the middle, there was an arcade, and in there, there was a large group from Milan: they were the Chinese, the communists. I knew some of them; they didn’t usually have issues with us, they had issues with the little fascists from the San Babila neighborhood. They couldn’t stand them: every time they met them, it was a fight, a real fight. I witnessed incredible scenes. It was a significant movement at the time. Besides, even now, I wouldn’t know how to define exactly what a Chinese is: it’s a kind of flower child transported to the ’80s, so with long hair but wearing Clarks because they are left-wing, and with tight jeans.”

RECORD SHOPS AND GOTH HAIRDRESSERS

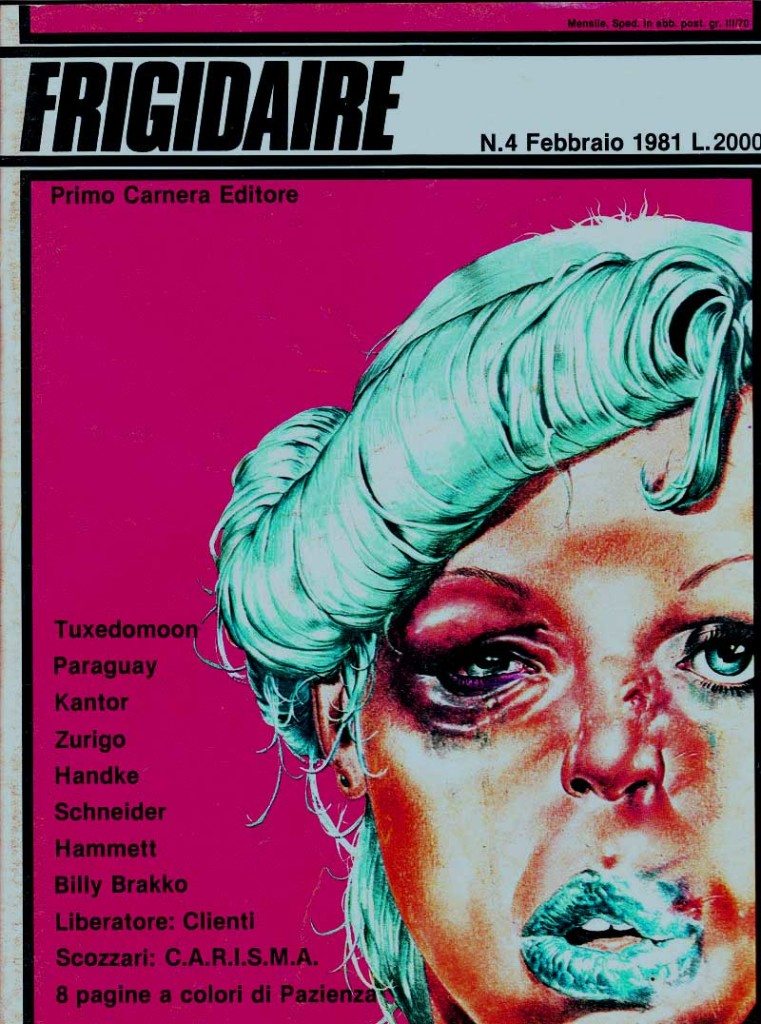

In addition to Virus, Helter Skelter, and Hysterika on Via Redi, other crucial places for the Milanese goth subculture were record shops. The most important were Fluxus No. 2 on Via Bergamo, Supporti Fonografici on Viale Cogni Zugna, which remained open for twenty years and also featured releases from tiny independent labels, and Ice Age. Emanuela Zini recalled, “Fluxus had an incredible setup. When you entered, there was a chair with cables, inspired by Francis Bacon’s painting of Innocent X.” Angela Valcavi remembered that Saturday afternoons required a ritual pilgrimage to see and buy new records. There were also goth hairdressers like Tato, who arrived hours late but then played Cure and Christian Death records, or Hair For Heroes. There were specialized clothing stores too, which we’ll delve into further in the following parts of this piece.

_ End of the second part of Kindred Creatures. In the next part of this article we will see the development of the most important gothzines and self-publications of the Italian 80s and 90s goth scene. But the very next article will be about the second part of our history of the color black. Stay Tuned through our new Instagram page!

Bibliography

If you enjoyed this article and are interested in delving deeper into the topic, you can find some bibliography in the following links. If you appreciate our content and would like to support the activities of our site, you can make purchases through these links, not necessarily limited to books listed in the bibliography but any kind of item. To do so, simply access the link and then fill your cart. Thanks to everyone!

Simone Tosoni, Emanuela Zuccalà, Italian Goth Subculture. Kindred Creatures and Other Dark Enactments 1982-1991

Images credits

Thanks to Simone Tosoni, Sergio di Meda, Joykix, Angela Valcavi, and Donatella Bartolomei for the additional info and the pictures.